I recently had the opportunity to bring together three diverse groups of people for a workshop, and the experience was truly inspiring. Mario Scharfbillig, a colleague at the Joint Research Centre EU Science, Research and Innovation of the EC, reached out to me for assistance with a workshop on the ValuesML project he was organising.

The workshop brought together experts on values from universities and research centres around the world (the first group) to brainstorm research project ideas that would contribute to a future algorithm identifying values in datasets. The ultimate goal of the ValuesML project is to provide policymakers in the EC (the second group) with a deeper understanding of citizens’ values, identities, and aspirations in order to better shape policies. To facilitate the workshop, I enlisted the help of my facilitator friends in Art of Hosting (the third group), Myrto Tsoukia and Maria Samuel Madureira Pinto. We did an outstanding job offering a ProAction Café and adapted the script live during the workshop.

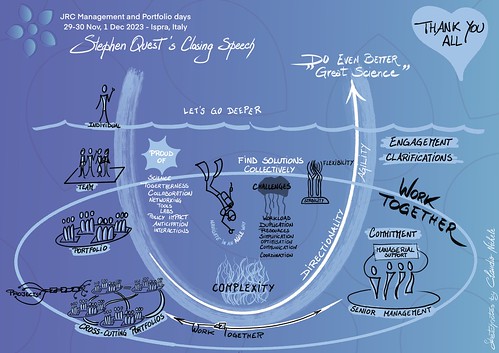

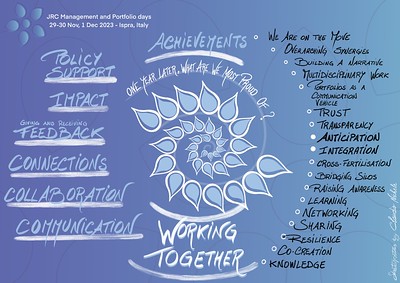

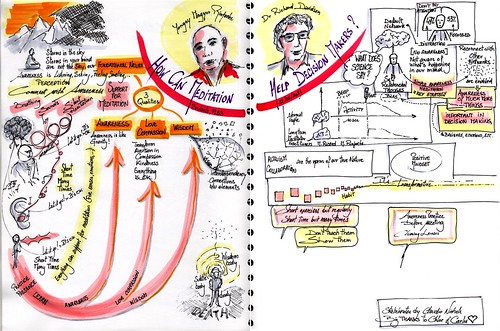

My main role was to take visual notes, capturing the outcomes of the participants’ conversations through graphic harvesting. What I noticed beyond the tangible outcomes of the workshop was the impact it had on all of us.

- Mario gained a better understanding of participatory methods for facilitating meaningful conversations

- My fellow facilitators working within European institutions recognised the importance of considering citizens’ values and identities in policy design

- Additionally, the researchers in the room had the opportunity to experiment with a participatory method for discussing their ideas.

Researchers’ curiosity and eagerness to see my graphic recording filled me with joy. For many, it was the first time they had seen visual notes taken live. What they saw were just the rough sketches on paper of their conversations. I sometimes had difficulty understanding their scientific jargon and I had to confirm with them my correct understanding or correct my approximations. The final result arrived a few hours later with a digital version reproducing my raw sketches on the iPad. I like to share here both versions in order to show that the live capture is not very far from the final version, certainly more beautiful and colorful, but the ideas are the same.

I hope that these visual notes will serve as a reminder of the richness of the conversations and the power of summarising complexity in a simple and elegant way.

It was a truly rewarding experience, and I look forward to future opportunities to facilitate and bring diverse groups of people together for meaningful conversations. And of course…to capture visually their conversations.

To better understand the ValuesML initiative and the purpose of the workshop you may read Mario’s post on Linkedin.